Tuberculosis (TB) is a serious infectious disease caused by bacteria belonging to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC). The most common and virulent member of this group is Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), also known as Koch’s bacillus. This article will provide a brief overview of the factors that determine the pathogenic capacity of the tubercle bacillus, and how they affect the host immune response and disease outcome.

Contents

What is the Tubercle Bacillus?

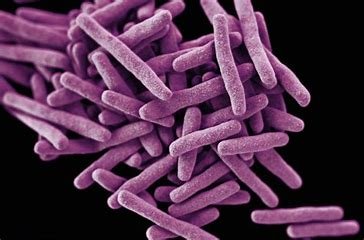

The tubercle bacillus is a small, rod-shaped bacterium that has a unique cell wall composed of lipids, such as mycolic acid and cord factor. These lipids make the bacterium resistant to drying, disinfectants, and staining by conventional methods. Instead, special acid-fast stains, such as Ziehl-Neelsen or auramine, are used to detect the tubercle bacillus under a microscope.

The tubercle bacillus is an obligate aerobe, meaning that it requires oxygen to grow and survive. It is also a slow-growing bacterium, with a generation time of 18-24 hours. This makes it difficult to culture and diagnose in the laboratory.

The tubercle bacillus is transmitted through the air by droplet nuclei that are generated when a person with pulmonary or laryngeal TB coughs, sneezes, shouts, or sings. These droplet nuclei can remain suspended in the air for several hours, and can be inhaled by another person who comes in contact with them. The droplet nuclei then reach the alveoli of the lungs, where they are engulfed by macrophages, which are immune cells that phagocytose foreign particles.

How Does the Tubercle Bacillus Cause Disease?

The pathogenesis of TB depends on several factors, such as the strain of the tubercle bacillus, the dose of infection, the route of entry, the host immune status, and the presence of co-infections or co-morbidities. However, a general overview of the stages of TB infection and disease can be summarized as follows:

- Primary TB: This occurs when a person is exposed to the tubercle bacillus for the first time. The bacteria multiply within the macrophages in the alveoli, and trigger an inflammatory response that attracts more immune cells to the site of infection. Some of these cells form granulomas, which are spherical structures that contain infected macrophages surrounded by lymphocytes and fibroblasts. Granulomas help to contain and isolate the bacteria from spreading to other tissues. However, some bacteria may escape from the granulomas and enter the bloodstream or lymphatic system, causing dissemination to other organs, such as the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, kidneys, bones, or meninges. This can result in severe complications, such as miliary TB or TB meningitis. Primary TB is usually asymptomatic or mild in most cases, and may resolve spontaneously or become latent.

- Latent TB: This occurs when the tubercle bacillus remains dormant within the granulomas for months or years without causing any symptoms or signs of disease. The person is not infectious at this stage, but may still test positive for TB infection by skin tests or blood tests. Latent TB can reactivate at any time if the host immune system becomes weakened by factors such as aging, malnutrition, HIV infection, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, cancer, immunosuppressive drugs, or stress.

- Secondary TB: This occurs when latent TB reactivates or when a person is re-infected by a new strain of tubercle bacillus. The bacteria break out of the granulomas and cause tissue damage and inflammation in various organs. The most common site of secondary TB is the lungs, where it causes pulmonary TB. Pulmonary TB is characterized by chronic coughing, hemoptysis (coughing up blood), chest pain, fever, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue. Pulmonary TB can also spread to other parts of the body through blood or lymphatic vessels. Secondary TB is more severe and more contagious than primary TB.

What Factors Influence the Pathogenic Capacity of the Tubercle Bacillus?

The pathogenic capacity of the tubercle bacillus is related to several factors that affect its ability to evade or manipulate the host immune response and cause disease. Some of these factors are:

- Genetic diversity: The MTBC consists of several closely related species and subspecies that have different host preferences and virulence levels. For example, M. tuberculosis sensu stricto is more adapted to humans than M. bovis, which causes TB in cattle and other animals. M. africanum causes TB mainly in Africa, while M. microti causes TB mainly in rodents. M. canetti is a rare and smooth variant of M. tuberculosis that causes TB mainly in the Horn of Africa. Within each species, there are also different strains that have different genetic mutations and variations that affect their pathogenicity. For example, some strains have deletions or insertions of genomic regions, such as the RD1 region, that encode for virulence factors, such as the ESAT-6 and CFP-10 proteins, which are involved in the secretion of bacterial molecules and the formation of granulomas. Some strains also have mutations in genes that affect their susceptibility or resistance to anti-TB drugs, such as the katG gene, which encodes for catalase-peroxidase, an enzyme that activates isoniazid, a first-line anti-TB drug.

- Lipid metabolism: The tubercle bacillus has a complex lipid metabolism that allows it to synthesize and modify various lipids that are essential for its survival and virulence. For example, mycolic acid is a long-chain fatty acid that forms the major component of the cell wall of the tubercle bacillus. Mycolic acid confers resistance to acid, alkali, detergents, and oxidative stress, and also modulates the host immune response by inhibiting phagosome-lysosome fusion, inducing apoptosis of macrophages, and suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cord factor is another lipid that is formed by the condensation of two molecules of mycolic acid with a disaccharide. Cord factor is responsible for the cording appearance of the tubercle bacillus under a microscope, and also contributes to its virulence by inducing granuloma formation, necrosis, and caseation (cheese-like appearance) of infected tissues.

- Antigenic variation: The tubercle bacillus can alter its antigenic profile by changing the expression or structure of its surface molecules, such as proteins, lipids, glycoproteins, or polysaccharides. This allows it to evade the recognition and elimination by the host immune system, and to adapt to different environmental conditions. For example, the tubercle bacillus can switch between different forms of its major surface glycoprotein, known as antigen 85 (Ag85), which is involved in the synthesis of cord factor and the attachment of the bacterium to host cells. Ag85 has three isoforms: Ag85A, Ag85B, and Ag85C, which differ in their amino acid sequences and immunogenicity. The tubercle bacillus can regulate the expression of these isoforms depending on the stage of infection and the host immune response.

Conclusion

The pathogenic capacity of the tubercle bacillus is related to its ability to survive and multiply within the host cells and tissues, and to evade or manipulate the host immune response. The tubercle bacillus has evolved various strategies to achieve this goal, such as genetic diversity, lipid metabolism, and antigenic variation. These factors determine the outcome of TB infection and disease in different hosts and settings.